Sandy Bottom

I turn off the tarmac into the dirt road and push as hard as I can on my mountain bike. The wheels whizz and spin, slid and slide, skip and bounce, until, inevitably, they get stuck in an expanse of lush, thick red sand, with the consistency of talcum powder.

Bulldust.

I swear at length and with feeling, get off and push. I battle through the patch, get on the bike again on the other side, and carry on through the trees, into the bushland. I hide my bike behind a big old fat boab, and start running. It is early morning, the land lies steaming under a tropical sun, and wallabies scatter before me as I run, barefoot through the sand. Black hawks circle overhead, following me from a distance and keeping a moody eye on me, in case I should show the great good grace of rolling over and carking it on the track, and providing them with a nice, juicey, fresh breakfast.

It feels a bit like I might, today. I've left it later than I would have wanted to, and the sun is beating down hard on my head. I've got neither hat nor water with me, because, dontcha know, I don't need those things.

Five km through the bush, along the edge of a salt marsh and past a water hole full of wading birds taking off at a screech when they feel me coming, I am given cause for reconsideration of that notion. I run from shade patch to tree shade patch as best as I can, and my head is slowly starting to cook. The end of the run is a well-deserved achievement, and going home for a drink and a rest-up appears like an attractive notion right now. But there's work to be done.

I retrieve my bike from the custodianship of the mighty boab, and ride till I get to the start of the drift of bulldust where I got stuck on the way in. Same as I have just about every other time, except on those rare occasions where it had rained the night before, and the water had packed down the fine sand enough to be able to ride over.

I stop, stand and glare at it. We have unfinished business, it and me.

Getting stuck up to my handlebars, or just about, every time I ride through here is shitting me to tears, and today is the day I have come to do something about it. So I get my hatchet out of my bag, and get to work.

There's a funny little kids' song I like to sing, that involves "going on a bear hunt", meeting obstacles such as "thick, squelchy mud", not being able to "go over it or under it", and, consequently, being forced to "go through it". I have often sung it with groups I have led through all manner of environments, mountains, forests, rivers and swamps, with little kids and big adults, and it stands as a moral guideline for life: if you can't avoid something, go through it. By extension it would be great to be able to apply that to some people I have known, the acquaintance with whom would have been greatly improved if, instead of diplomatically going around them and avoiding the pain in the arse that they were, it would have been possible to go straight through them, in the process preferably flattening them and comprehensively grinding them into the ground.

The difficulty of negotiating the section of bulldust on the track is compounded by the fact that it appears immediately behind a bend in the track, and that the inside corner of that bend is completely overgrown with runners, shoots, saplings and branches of sundry extraction. If it wasn't for them it might, possibly just might, be feasible to stick to the hard shoulder of the track, skirt along the edge of the loose sand, and get through it in one piece. Therefore, I have come equipped to clear the edge.

I go to work with the hatchet, hacking away at the base of small trees, chopping into thick, overhanging branches, and slicing through shoots and runners. Within seconds the sweat is pouring off me like rivulets of rain in the wet season, which it should by rights be right now, but which is so far giving no sign of any inclination to start: the sky continues to be a hard, glaring blue day after day, and there are no clouds anywhere within cooee. As I work I become aware that I am, potentially, engaging in a type of exertion that could lead to trouble. The temperature is very nearly 40 degrees in the shade. In the sun it would boil and explode any thermometer you'd deign to try to use. The sun is sitting overhead like a mobile smelting furnace, and the air is wobbling with still, standing heat waves. It vaguely occurs to me that this might not, in actual fact, be such a brilliant idea, and that if I croaked here on the track, in the middle of nowhere, it would take a long time before anyone found my desiccated and dehydrated dead body.

People die in these parts with depressing frequency. Near another place where I lived previously, in a very similar setting, in recent years an enterprising English adventurer aspired to ride a bike through The Back Of The Black Stump, to raise money and awareness for some worthy cause or other. He came over a bit faint, got a bit hot under the collar, fell off his bike beset by thirst, and crawled under a tree where he died of lack of water. Less than two kilometres away there was a deep, cool permanent waterhole, full of ducks, geese, ibises, barramundi, turtles, and the odd freshwater crocodile.

I wipe the sweat out of my eyes, survey my progress so far, and carry on with grim determination. I won't melt here and die from internal organ failure, caused by overheating, dehydration, and energy depletion up to the point where protein, i.e. muscle and organs, get metabolised for energy recruitment, which causes metabolic collapse and death.

Because I have a secret weapon.

Everyone knows that camels are exceptionally well adapted to surviving in waterless environments. It is a widely held notion that this is because they carry water in their hump or humps on their backs, like a long-range fuel tank on a fourwheel drive, and that they live on that for weeks at a time. While this is a charming idea that is often bandied about as gospel, it is as wrong as billy-o.

A camel's hump is not made of water. It is, in actual fact, made of fat. And camels can live on it for extended periods of time because it does two things. One, fat metabolises into energy, and allows the camel to keep plodding onwards on its great big flat feet without slowing down. And two, the metabolisation of fat for energy creates a byproduct, and that, as it so happens, is water. Enough of it to meet the requirements of the organism producing it, at least for some time.

I am not a camel.

I may, in a bad light, appear to have a hunchback, but it is not a hump.

I have big, flat feet, but they are not round, and I have more than two big toes sticking out.

I have a big nose and evil-looking round eyes, but they are not, unfortunately, equipped with nostrils that can be closed to the world, or a third eyelid to keep sand and dust out.

Moreover, I don't bite and randomly kick out at people, or, at least, not at all people.

But I am fat adapted.

I live on fat. I only eat animal products, and specifically those with a high fat content: meat, seafood, eggs, cheese. Nothing else. This is sometimes referred to as the Mesech diet, or, occasionally by confabulating doctors, clinging desperately to deeply flawed textbooks and Directives By Management, as madness.

Nevertheless, it is standing me in good stead now. In spite of the gallons of water I am shedding in sweat I am not thirsty, and after the first five minutes of warming up I settle into a steady work routine, swinging the hatchet like a man possessed, and ploughing my way through the overgrowth along the track. This kind of work is second nature to me, I used to be a Parks and Wildlife Ranger and environmental worker, and this sort of stuff was my stock in trade.

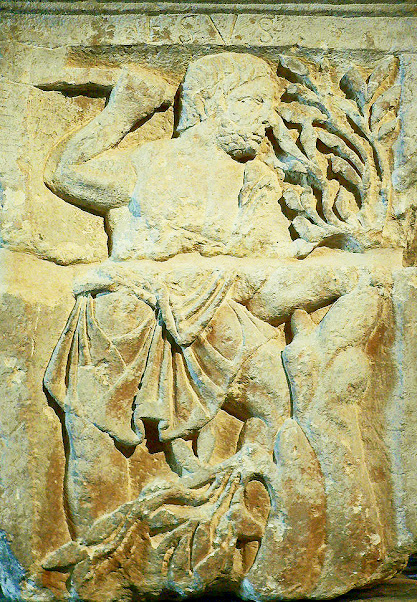

An image comes to me, through the hazy vibrations of the hot air: there was an old Celtic god who was depicted as being hard at work with an axe, cutting down trees. His name was Esus, NOT Jesus, and, from his general pictographic representation, it is widely believed by scholars in Celtic culture that he was, in actual fact, the God Of Cleaning Up The Backyard, And When You're finished With That Clean The Gutters And Do The Dishes. This notion appears to be confirmed by the fellow's habitual appearance, in engravings, as disgruntled, badly put upon, and pussy-whipped. Recent archaeological digs have unearthed altars with dedications that suggest he was also, in certain parts, revered as the god of Fuck This I'm Going To The Pub.

It occurs to me that, right now, I am doing The Works Of Esus, a notion that has a high likelihood of pissing off any number and grouping of evangelical christians, who would be sure to think it blasphemous. This is undoubtedly a good thing, and I take heart from the notion to push through, clearing vegetation until, finally at long last, the corner of the track and the shoulder lie clear before me. Behind me lies a trail of sweat-soaked dirt a meter wide and twenty meters long. Small birds come flying in from out of nowhere to drink from the puddles of my sweat, and a passing-by lungfish jumps into one of them with a big smile on his face. Good on him. Be my guest, why don't you.

In front of me, stretching out into the middle distance like the gaping maws of a crocodile encouraging you to think that the water looks great and inviting and it's probably not that bad really, lies a spread of white, yellow and red sand, by this time scalding hot under the feet. And next to it, there is now a hard shoulder, denuded of vegetation.

I eye it off, and nod to myself. Time to give it a crack.

I get my bike, retreat back up the track a bit for a good run-up, and take a deep breath.

Then I stand up on the pedals and push. Hard.

I make it around the corner without losing too much speed, and line up for The Great Sandy Desert.

I fly over the first section of solid edge. Encounter a low-lying wash-out of a dry creek bed.

Skid and fishtail through the yellow sand.

Bounce back up and over its steep but hard bank on the other side.

Catch my front wheel in a sink of fine bulldust, counter-steer hard to the other side, wrench the handlebars, and slip back out of it.

Onto hard red dirt, and onto gravel, and, finally, to the end of the track, where black tarmac starts.

I made it.

Time well spent.

I would have been pretty mightily pissed off if, after all that, I hadn't been able to ride out.

I turn and head home. A drink seems like a good idea.

Comments

Post a Comment